|

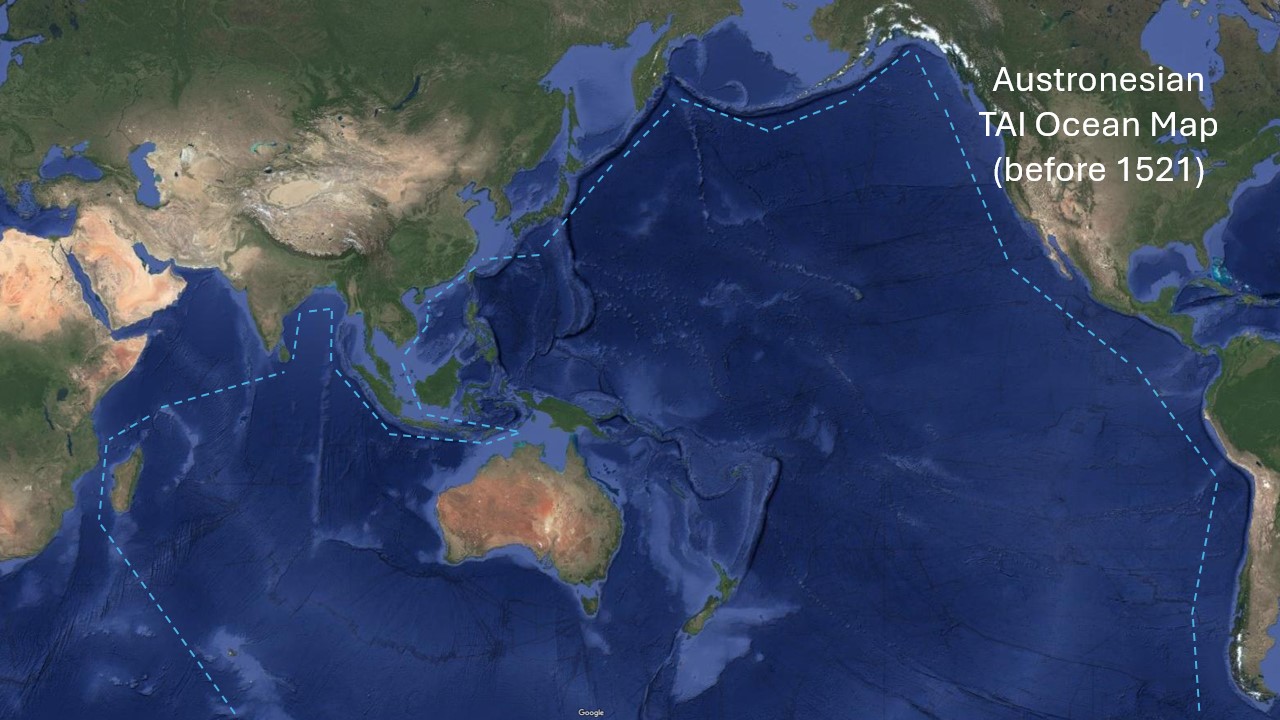

Austronesian TAI Ocean Map (before 1521) |

|---|

|

Given the widespread presence of “tai” and its derivatives across Polynesian, Micronesian, and Austronesian languages, it is highly likely that Austronesians referred to the vast body of water they navigated as “Tai” (or its regional variations) for thousands of years...

- The Proto-Polynesian root tai, meaning sea, saltwater, or tide, appears consistently across all major Austronesian languages.

- This suggests that early Austronesians conceptualized the ocean as a living, moving entity governed by tides and currents rather than a fixed, land-based space.

- Unlike European civilizations that named the ocean as a barrier or border, Austronesians likely viewed Tai as a highway, a provider, and a sacred force.

- The Polynesian concept of Moana (deep sea) also reflects this—showing that Austronesians had a layered understanding of oceanic spaces:

-

- Tai = Coastal or navigable sea- Moana = Deep ocean beyond sight of land

-

- The consistency of tai and its derivatives in Malagasy (ranomasina), Hawaiian (kai), and Māori (tai) shows that Austronesians carried this name with them as they expanded across the Pacific.

- As they traveled, they likely referred to the ocean not as a single “named” entity like “Pacific” but as a fluid, interconnected Tai—a space they understood deeply through generations of seafaring.

- Since Austronesians saw the sea as their home, they likely thought of themselves as part of the Tai—a civilization connected by water, not separated by it.

- The Spanish and Europeans saw the Pacific as Mare Pacificum (a peaceful sea), but Austronesians saw it as Tai—their living, dynamic world.

- If the Austronesians of the Philippines, Polynesia, and Madagascar conceptualized the ocean as Tai, then the 1734 Velarde Map was not just a Spanish colonial map but an Austronesian map of Tai.

- The Velarde 2025 Map, which renames the Pacific as the American Pacific Ocean, follows a long tradition of renaming Austronesian waters—first by the Spanish (Iberian Lake), then by the Americans, and now contested by China.

- The real question is: Can Austronesians reclaim “Tai” as their historical domain, just as they did for thousands of years before colonization?

Show more

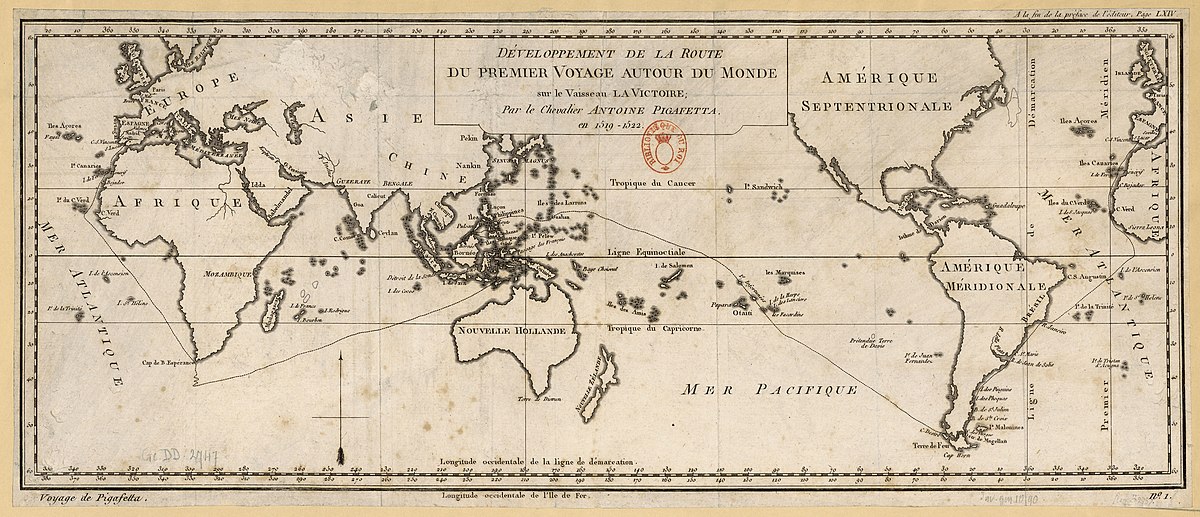

Mare Pacificum (1521) → Spanish Lake → Spanish-American Pacific Ocean (until 1898) |

|---|

SOURCE: WIKIMEDIA.ORG For almost 500 years, the Pacific Ocean was known not just as “Mare Pacificum” (the name given by Magellan) but as the Spanish Lake—an Iberian American Ocean governed by Spain and Portugal from 1500 to 1898. This body of water should now be called the American Pacific Ocean. It stretched:

|

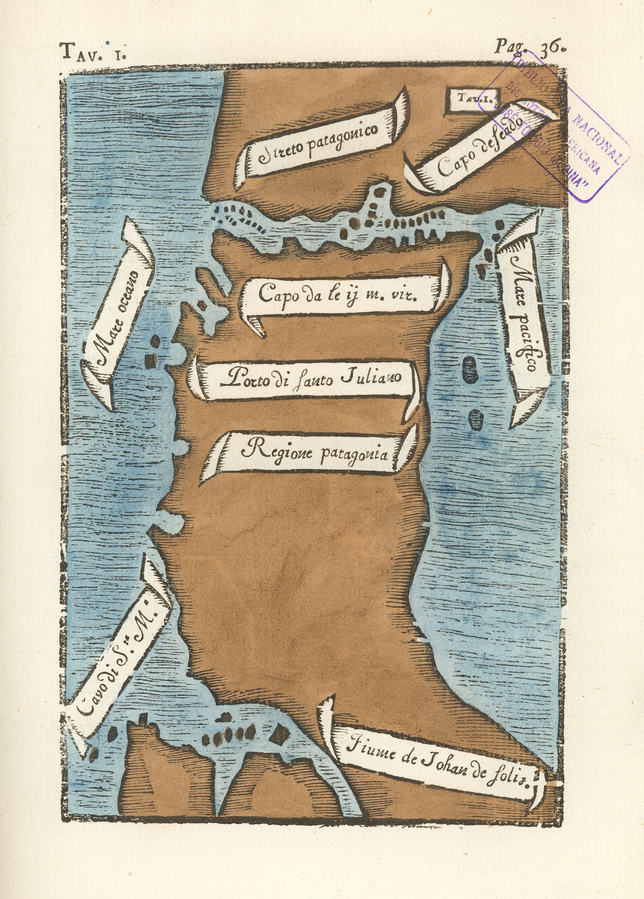

The First Map of the Strait of Magellan (1520) |

|---|

SOURCE: WIKIMEDIA.ORG SOURCE: WIKIMEDIA.ORG

The first circumnavigation of the globe was the voyage of 1519-22 by the Portuguese navigator Ferdinand Magellan (1480-1521), undertaken in the service of Spain. The only known first-hand account of the voyage is the journal by Venetian nobleman and scholar Antonio Pigafetta (circa 1480-1534). Four manuscript versions of Pigafetta’s journal survive, three in French and one in Italian. Pigafetta also made 23 beautiful, hand-drawn color maps, a complete set of which accompanies each of the manuscripts. Shown here is Pigafetta’s map of the Strait of Magellan, as reproduced in Carlo Amoretti’s 1800 edition of the only Pigafetta manuscript in ltalian. Amoretti (1741-1816) was an Italian priest, writer, scholar, and scientist, who, as a conservator at the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan, discovered the manuscript, which was long thought to be lost. Amoretti published the Italian text with notes in 1800, and a French translation the following year. The map depicts the southern part of South America, including the Strait of Magellan, discovered on the voyage. Discovery and exploration; Magellan, Strait of (Chile and Argentina); Tierra del Fuego (Argentina and Chile). |

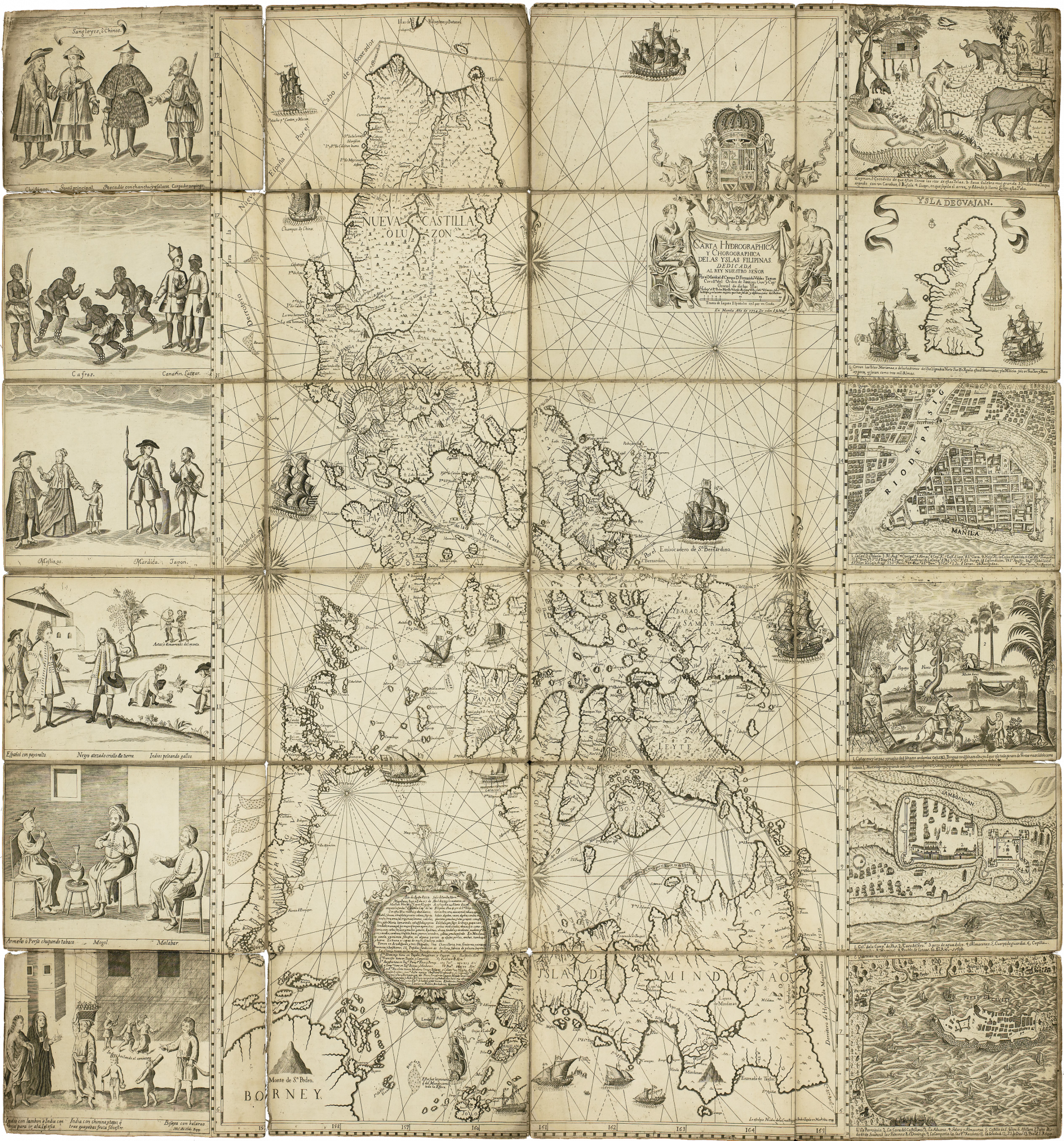

Murillo Velarde (1734) |

|---|

|

The Carta Hydrographica y Chorographica de las Yslas Filipinas, first published in Manila in 1734, is revered as the “Mother of All Philippine Maps.” Created under the direction of Spanish Jesuit Friar Pedro Murillo Velarde, it was drawn by Francisco Suarez and engraved by Nicolas dela Cruz Bagay—making it the first scientific map of the entire Philippine archipelago.

Unlike other colonial maps that solely reflected the perspectives of colonizers, this is the only known colonial-era map created through a collaboration between an enlightened colonizer and the colonized. It is a rare historical document where Spanish cartographic traditions merged with Filipino artistry, indigenous knowledge, and local craftsmanship. Flanked by twelve vignettes depicting Filipino life, culture, and landscapes, the map also affirms the presence of Panacot (Scarborough Shoal) and Los Bajos de Paragua (Spratly Islands) as part of the Philippines.

The Murillo Velarde 1734 Map is more than just a colonial artifact—it is a testament to the indigenous Austronesian heritage that predates Spanish rule. The vignettes illustrate the diverse cultures of Austronesian Filipinos, showcasing their seafaring skills, trading networks, and governance systems—an enduring legacy of a people deeply connected to the sea and their land.

As a 99.6% Austronesian Filipino, Mel Velasco Velarde embodies this ancestral heritage, making his reclamation of the map not just an act of historical preservation, but a reaffirmation of Filipino identity and sovereignty. Once a tool of conquest, the map now stands as proof of the resilience, continuity, and rightful ownership of the Philippine archipelago by its indigenous people.

The Murillo Velarde 1734 Map was a crucial piece of evidence in the Philippines’ case filed against China at the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) constituted under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Its 2016 Arbitral Award not only reaffirmed the Philippines' maritime entitlements, reinforcing the country’s rights over resources within our exclusive economic zone and continental shelf in the West Philippine Sea, but also won for the Free World the freedom of navigation for the whole South China Sea.

For 280 years, the Murillo Velarde 1734 Map was privately held by British nobility, forming part of the Duke of Northumberland’s collection in the United Kingdom. It was kept at Newcastle Estate and later Alnwick Castle—a historic fortress that gained worldwide recognition as Hogwarts in the Harry Potter movies

In 2014, Supreme Court Senior Associate Justice Antonio T. Carpio discovered that the heirloom map was scheduled for auction at Sotheby's London by Ralph George Algernon Percy, the 12th Duke of Northumberland. Recognizing its crucial role in Philippine history and maritime sovereignty, Justice Carpio urged both public and private entities, including Filipino entrepreneur and educator Mel Velasco Velarde, to bid for the map and bring it back to the Philippines.

For three years (2014-2017), the map remained in London, on standby in case the Arbitral Tribunal needed to see the actual document, not just a facsimile. After complying with British export regulations, the Murillo Velarde 1734 Map finally received clearance in 2017, allowing it to be repatriated to the Philippines—a full 283 years after its copperplates were created in Manila.

On December 6, 2024, in a historic handover at Malacañan Palace, the government of the Republic of the Philippines, represented by President Ferdinand R. Marcos Jr. and First Lady Marie Louise Araneta-Marcos, officially received the Murillo Velarde 1734 Map.

Now permanently displayed at the National Library of the Philippines, the map is accessible to the public free of charge—a condition explicitly set by Mr. Velarde in his deed of donation to ensure every Filipino has access to this national treasure.

To further preserve and amplify its historical significance, Mr. Velarde retained ownership of the digital rights, ensuring its mass distribution worldwide. This guarantees that Filipinos, scholars, and the global community can study, share, and use the map freely as an enduring symbol of Philippine sovereignty and heritage.

Additionally, commemorative copies of the map are being distributed to government agencies, academic institutions, and private organizations to raise national consciousness about Philippine sovereignty, cultural heritage, and history.

“As my gift to the Filipino people, this 300-year-old Murillo Velarde 1734 Map is a declaration of my gratitude for the privilege of being a Filipino, blessed with a sovereign, democratic, and free homeland. Let this be a beacon of our shared history and an inspiration for generations to come.”

Mel Velasco Velarde

August 9, 2024

Show more

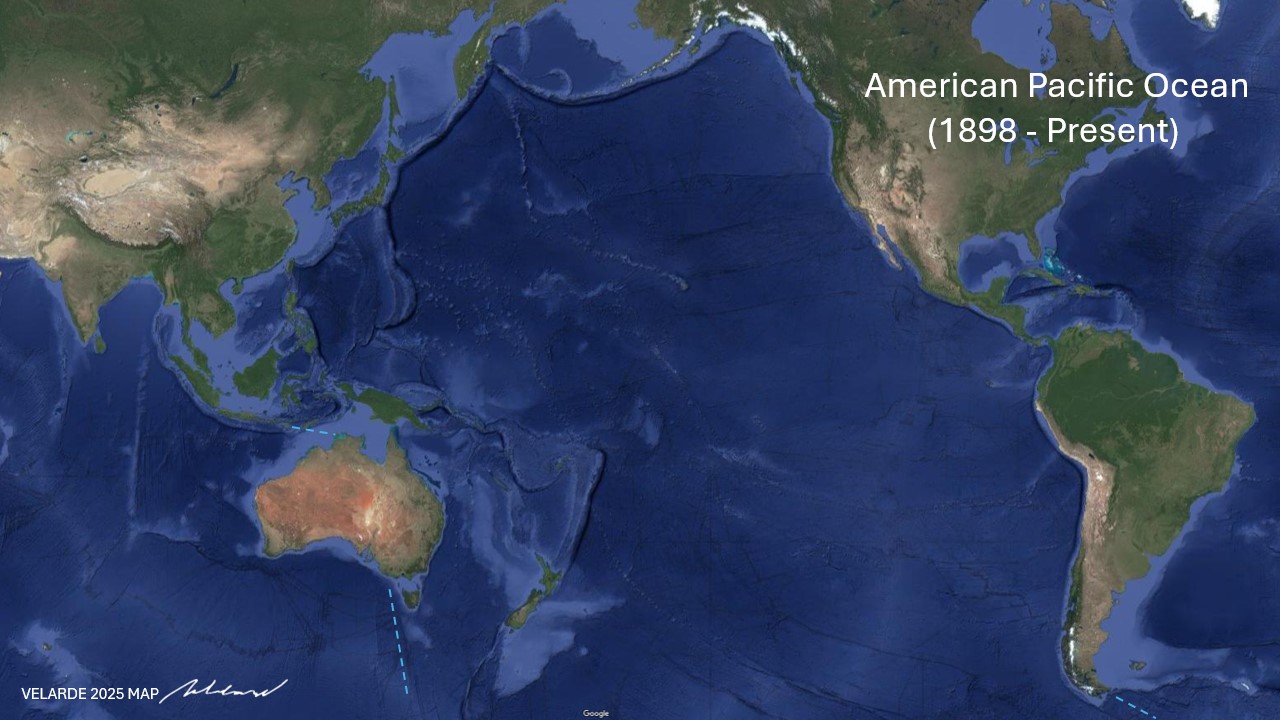

American Pacific Ocean (1898-Present)Velarde 2025 Map Proposal |

|---|

According to the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO)—the body that sets the official boundaries for the world’s oceans—the Pacific Ocean is defined as the largest of Earth’s oceanic divisions, covering roughly 165 million square kilometers. Its official boundaries are as follows: According to the International Hydrographic Organization (IHO)—the body that sets the official boundaries for the world’s oceans—the Pacific Ocean is defined as the largest of Earth’s oceanic divisions, covering roughly 165 million square kilometers. Its official boundaries are as follows:

Within these vast limits, the Pacific Ocean encompasses numerous subregions and marginal seas, such as the Sea of Japan, the East China Sea, the Coral Sea, and the Tasman Sea, each contributing to its complex and diverse marine environment. This comprehensive coverage, as established by the IHO, not only highlights the immense scale of the Pacific Ocean but also its critical role in global climate, trade, and biodiversity. The definition is based on the International Hydrographic Organization’s (IHO) publication, Limits of Oceans and Seas. You can review further details on the official IHO website at: |

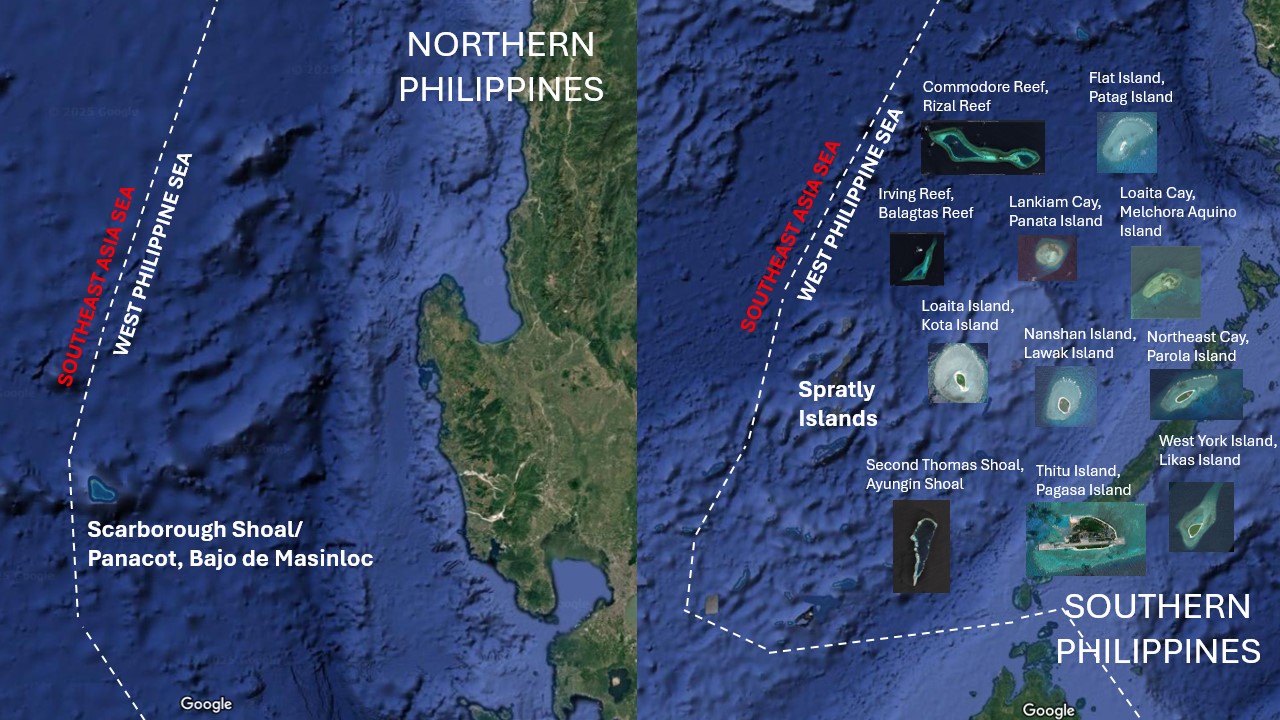

Southeast Asia Sea/West Philippine Sea (part of the American Pacific Ocean) |

|---|

|

Spate, O.H.K. (1979). The Spanish Lake. Australian National University Press. |

|

|---|---|

|

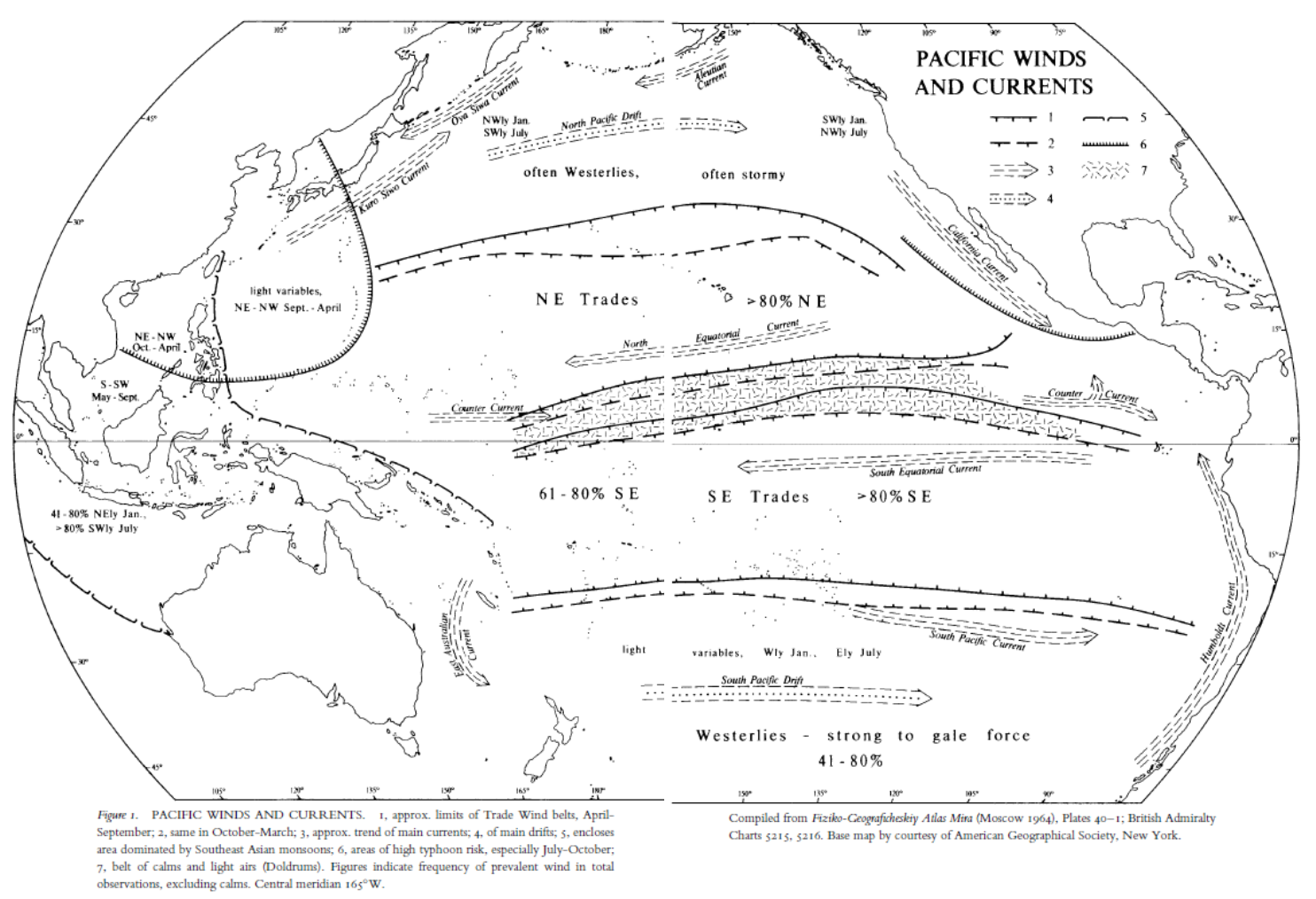

The map titled "PACIFIC WINDS AND CURRENTS" provides a geographic representation of the wind patterns and ocean currents in the Pacific Ocean, illustrating trade wind belts, prevailing oceanic drifts, typhoon-prone areas, and seasonal variations in atmospheric circulation.

The map is compiled from "Fiziko-Geograficheskiy Atlas Mira" (Moscow, 1964), specifically Plates 40-1, and British Admiralty Charts 5215 and 5216. It was developed using extensive meteorological and oceanographic data to highlight wind frequency, the direction of ocean currents, and regions affected by strong weather phenomena. The enclosed areas indicate the influence of Southeast Asian monsoons and typhoon activity, particularly during July to October. Trade wind belts are marked with approximate seasonal limits, and counter-currents are depicted to show the complexity of Pacific Ocean circulation. The base map is provided by the American Geographical Society, New York, ensuring a reliable geographic foundation for the representation of global wind and oceanic trends.

Show more

|

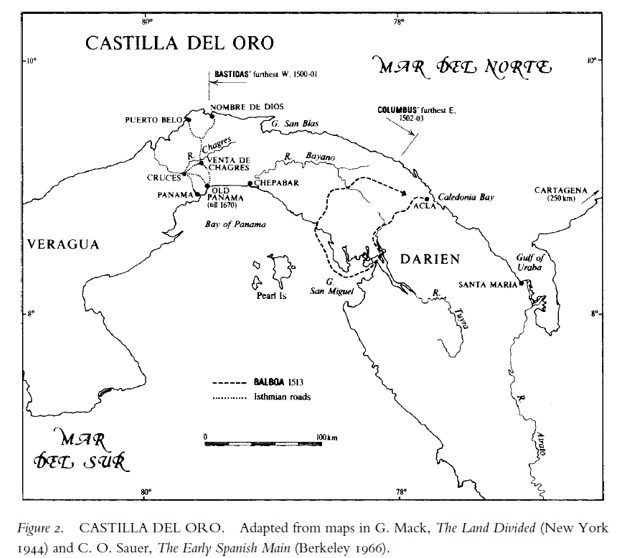

The map is titled "CASTILLA DEL ORO" and is adapted from maps found in two sources:

1. G. Mack, The Land Divided (New York, 1944)

2. C. O. Sauer, The Early Spanish Main (Berkeley, 1966)

These sources were used to create the historical representation of the region during the early Spanish colonial period.

"CASTILLA DEL ORO" represents a historical geographic depiction of the early Spanish exploration and colonization of Central America, specifically the Isthmus of Panama and surrounding regions. The sources cited for its adaptation are:

G. Mack, The Land Divided (New York, 1944) – This book is a historical account of the exploration, settlement, and geopolitical importance of the Isthmus of Panama. It details the Spanish conquest and the role the isthmus played in connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, which later influenced the construction of the Panama Canal.

C. O. Sauer, The Early Spanish Main (Berkeley, 1966) – A significant work on the Spanish colonization of the Caribbean and Central America, this book provides insights into early Spanish settlements, trade routes, indigenous encounters, and exploration efforts, including Vasco Núñez de Balboa’s crossing of the isthmus in 1513.

Key features of the map:

- Castilla del Oro: The Spanish name for the colonial territory that included present-day Panama and parts of Colombia.

- Mar del Norte & Mar del Sur: The map labels the Atlantic Ocean as "Mar del Norte" (North Sea) and the Pacific Ocean as "Mar del Sur" (South Sea), following early Spanish navigation terminology.

- Darien: A significant area for early Spanish settlement, including Santa María la Antigua del Darién, the first permanent European settlement in mainland America.

- Balboa’s Route (1513): The map highlights the path taken by Vasco Núñez de Balboa when he became the first European to see the Pacific Ocean from the New World.

- Colonial Roads: Dashed lines indicate early isthmian roads, which played a crucial role in trade and transportation between the coasts.

- Explorers’ Routes: The furthest west reached by Rodrigo de Bastidas (1500-1501) and the furthest east reached by Christopher Columbus (1502-1503) are marked, showing the extent of early Spanish navigation in the region.

- Important Settlements and Landmarks: Locations such as Nombre de Dios, Puerto Belo (Portobelo), and Old Panama (destroyed in 1670) are included, showcasing Spanish efforts to establish control and facilitate gold transport.

This map is valuable for understanding the early Spanish colonial expansion in the Americas, the significance of the Isthmus of Panama in global trade, and the routes taken by key explorers of the 16th century.

Show more

|

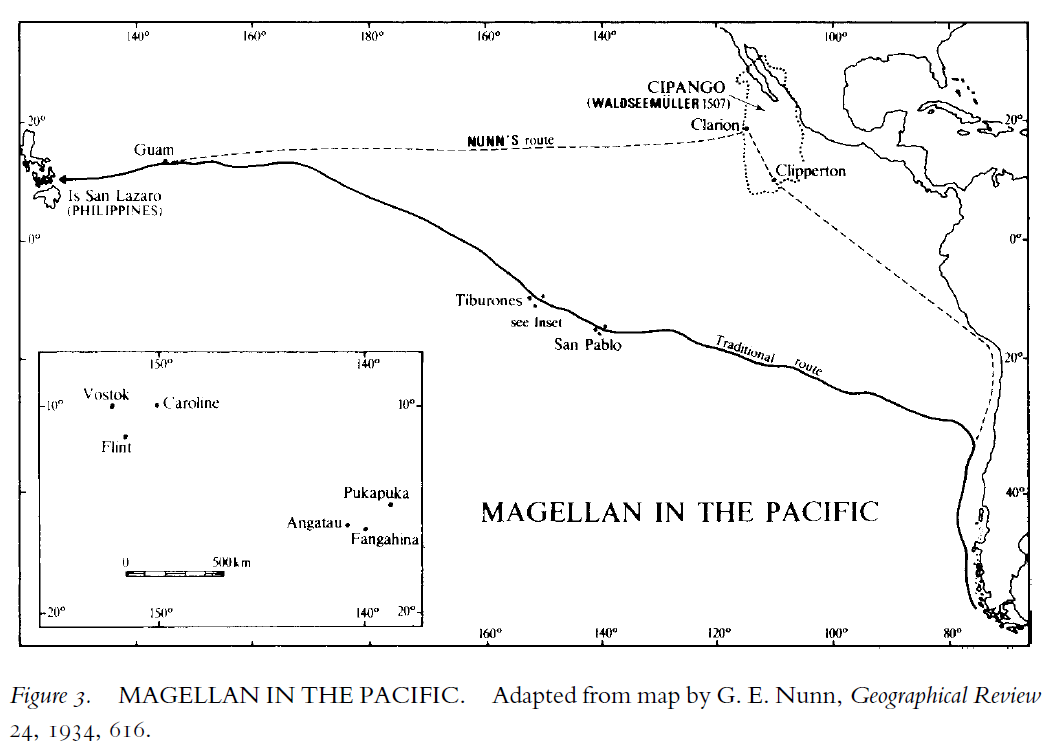

The map in the image is titled "MAGELLAN IN THE PACIFIC" and is adapted from a map by G. E. Nunn, originally published in the Geographical Review, Volume 24, in the year 1934, on page 616.

This suggests that the map is based on historical research about Ferdinand Magellan's journey across the Pacific. G.E. Nunn was known for his work on historical cartography and early explorations, and this particular map likely visualizes Magellan's navigation route through the Pacific during his 1519-1521 expedition.

Show more

|

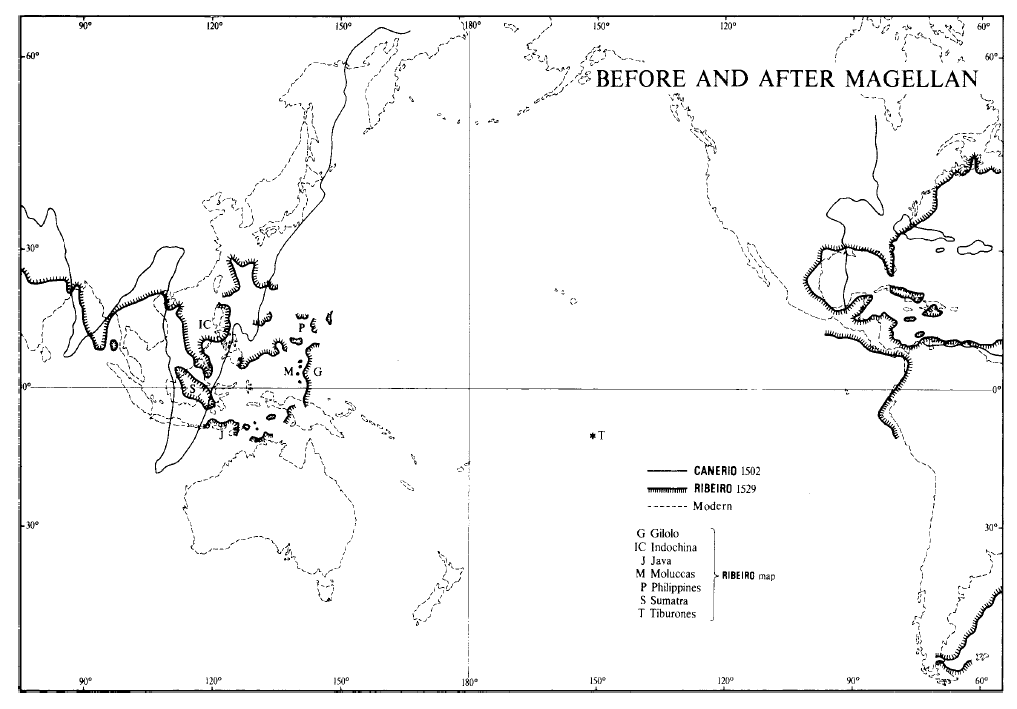

The map titled "BEFORE AND AFTER MAGELLAN" visually represents geographic knowledge of the world before and after Ferdinand Magellan's expedition, highlighting early cartographic interpretations of Asia and the Pacific.

The map is based on historical cartography, featuring sources such as Canerio's 1502 map and Ribeiro's 1529 map, contrasted with modern geographical boundaries. Canerio's map represents early European perceptions of maritime routes and landmasses before Magellan's circumnavigation, while Ribeiro's map reflects knowledge gained from subsequent explorations, including the more accurate placement of the Philippines, Moluccas, and surrounding islands. The comparison underscores the evolution of geographic understanding in the Age of Exploration, illustrating how early maps contained distortions that were progressively corrected through navigational discoveries. Key locations such as Gilolo, Java, Sumatra, and Indochina are marked, showing their significance in early European exploration efforts. The map serves as a historical reference for the impact of Magellan’s voyage on world mapping.

Show more

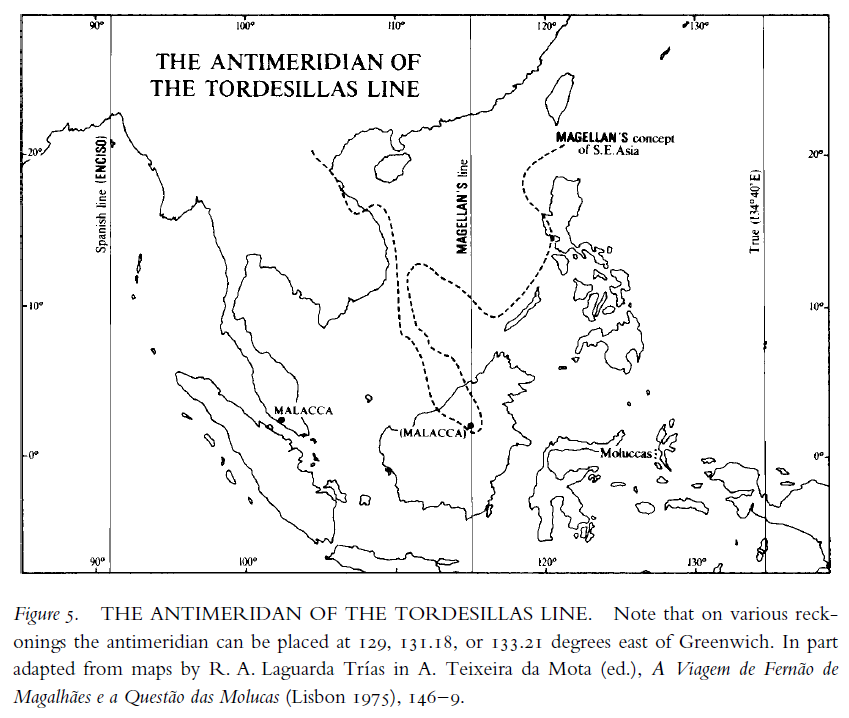

Figure 5. THE ANTIMERIDAN OF TORDESILLAS LINE. Page 56 |

The map titled "THE ANTIMERIDIAN OF THE TORDESILLAS LINE" illustrates the division of the world between Spain and Portugal as defined by the Treaty of Tordesillas, with a focus on its antimeridian, which determined territorial claims in the East.

The map is an adaptation from historical sources, particularly the work of R. A. Laguarda Trías and A. Teixeira da Mota, and presents different possible placements of the antimeridian at 129°, 131.18°, or 133.21° east of Greenwich. This variation reflects the difficulties in accurately determining the boundary due to limitations in early cartographic techniques. It highlights Magellan’s perception of Southeast Asia and his navigational route towards the Moluccas, a crucial region for the spice trade. The map also depicts the Spanish and Portuguese spheres of influence, with Malacca and the Moluccas as key strategic locations. The division of these territories played a major role in the geopolitical conflicts and negotiations between Spain and Portugal in their quest for control over the lucrative spice trade.

Show more

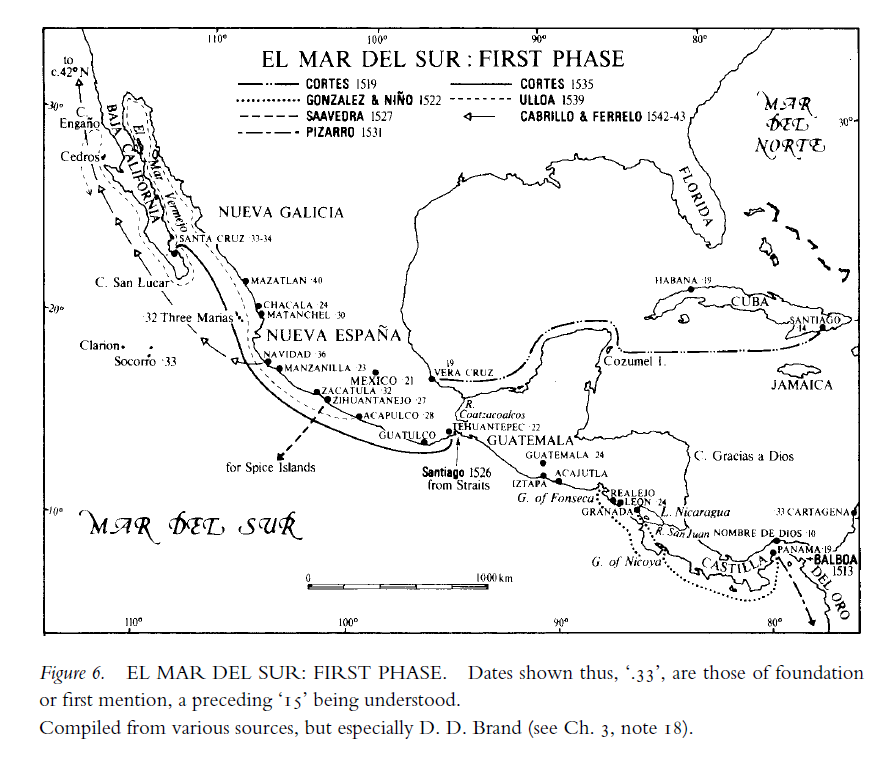

Figure 6. EL MAR DEL SUR : FIRST PHASE. Page 64 |

The map titled "EL MAR DEL SUR: FIRST PHASE" illustrates the early Spanish explorations and expeditions across the Pacific Ocean from the Americas. It highlights the routes of key explorers such as Cortés (1519 and 1535), González & Niño (1522), Saavedra (1527), Pizarro (1531), Ulloa (1539), and Cabrillo & Ferrelo (1542-1543).

This map details Spanish colonial expansion along the western coast of the Americas, particularly in Nueva España (Mexico) and Nueva Galicia, as well as their ambitions to reach the Spice Islands. The dotted and solid lines represent different expedition routes, illustrating the progress of Spanish maritime exploration in the Pacific.

Key locations such as Veracruz, Acapulco, Panama, and Balboa's 1513 expedition to the Pacific are marked, showcasing the importance of these areas in Spain’s strategy for Pacific exploration and expansion.

Show more

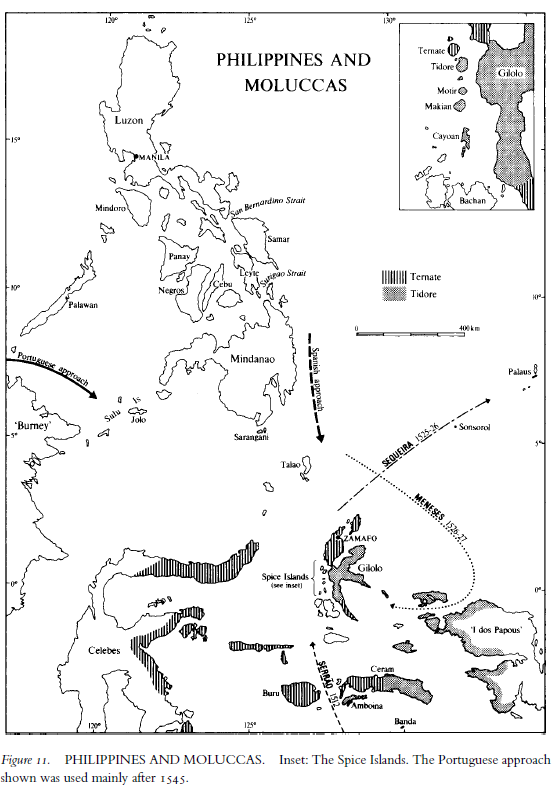

Figure 11. PHILIPPINES AND MOLUCCAS. Page 88 |

The map, titled "PHILIPPINES AND MOLUCCAS," provides a geographic depiction of the Philippines and the Spice Islands (Moluccas), focusing on the competing Spanish and Portuguese claims over the region. The inset map details the key islands of the Moluccas, including Ternate and Tidore, which were central to the spice trade.

This map highlights the strategic importance of the region, with markings of Portuguese and Spanish approaches, reflecting their respective colonial routes. The map also includes the routes of early European explorers, such as those of the Spanish expedition of 1526 (Loaysa) and 1527 (Saavedra), showing their attempts to establish control over the Spice Islands. The geopolitical significance of these islands was immense, as they were the only source of valuable spices such as cloves and nutmeg, making them a major point of contention between the two Iberian powers.

Show more

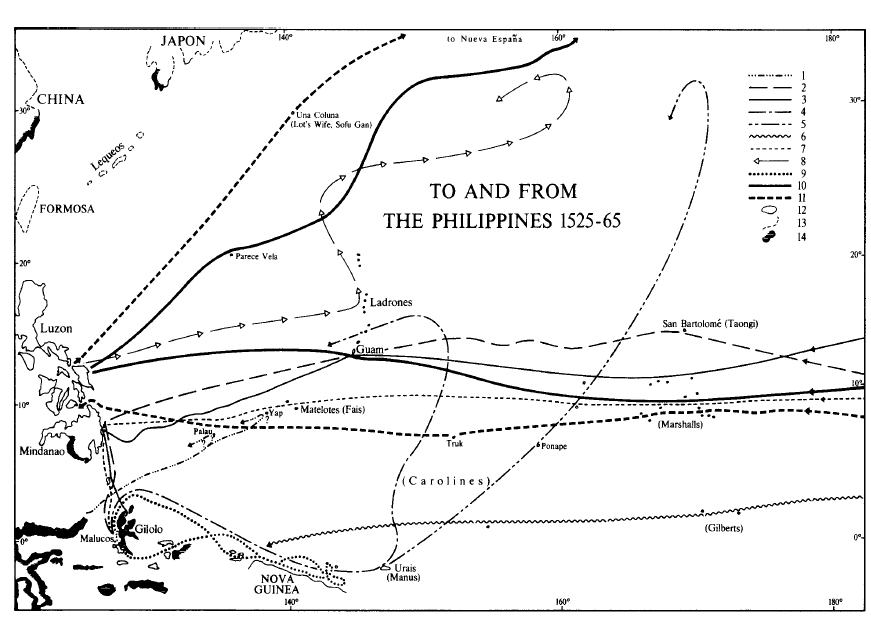

Figure 12. TO AND FROM THE PHILIPPINES 1525-65. Page 92 |

The map titled "TO AND FROM THE PHILIPPINES 1525-65" illustrates the early maritime routes used by Spanish explorers and navigators between the Philippines and various locations, including Nueva España (Mexico), China, Japan, and the Pacific islands.

The map highlights key navigation routes taken by Spanish galleons, showing outbound and return paths. It features important locations such as Luzon, Mindanao, the Ladrones (Mariana Islands), Guam, the Moluccas, Nova Guinea, and various islands in the Caroline and Marshall archipelagos.

The thick solid line represents the main route of the Manila-Acapulco Galleon Trade, while other dashed and dotted lines indicate alternative or exploratory routes during the period. These routes played a crucial role in Spain’s colonial expansion, trade, and influence in the Asia-Pacific region.

Show more

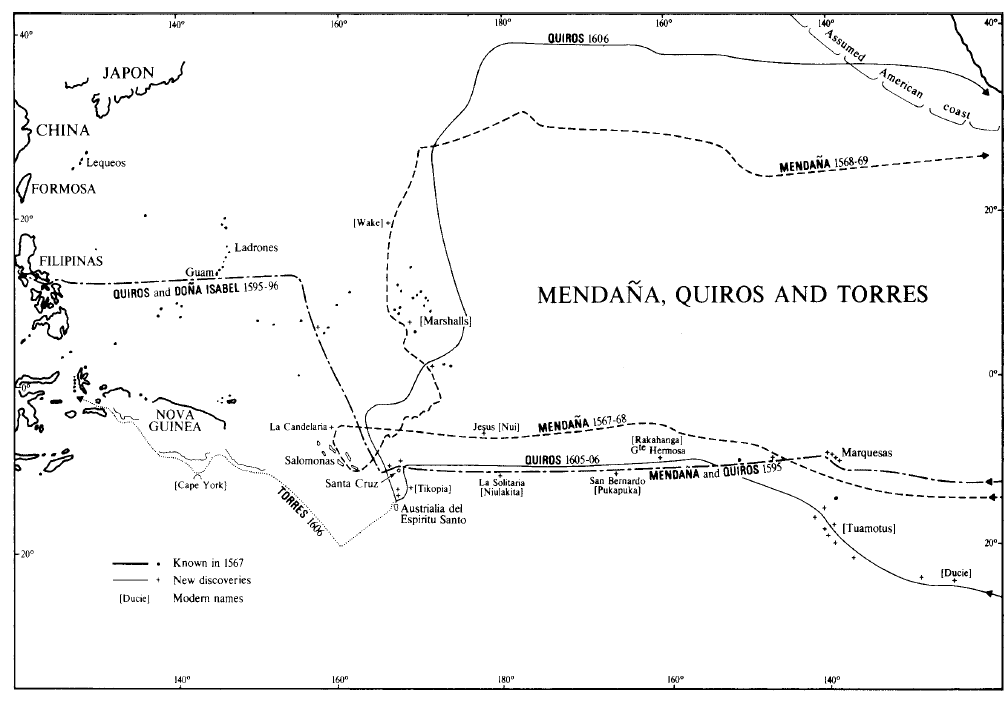

Figure 14. MENDAÑA, QUIROS AND TORRES. Page 120 |

The map titled "MENDAÑA, QUIROS AND TORRES" illustrates the exploration routes taken by Spanish navigators Alvaro de Mendaña, Pedro Fernandes de Queirós (Quiros), and Luis Váez de Torres in the late 16th and early 17th centuries.

The map depicts various voyages, including those of Mendaña (1568-69, 1595), Quiros (1605-06), and Torres (1606). These expeditions contributed to the European discovery of several islands in the Pacific, such as the Marquesas, Solomons, Santa Cruz, and Espiritu Santo.

The dashed and solid lines represent known routes, new discoveries, and modern names of locations. The Torres Strait, which separates Australia and Papua New Guinea, is named after Torres, who sailed through it in 1606.

Show more

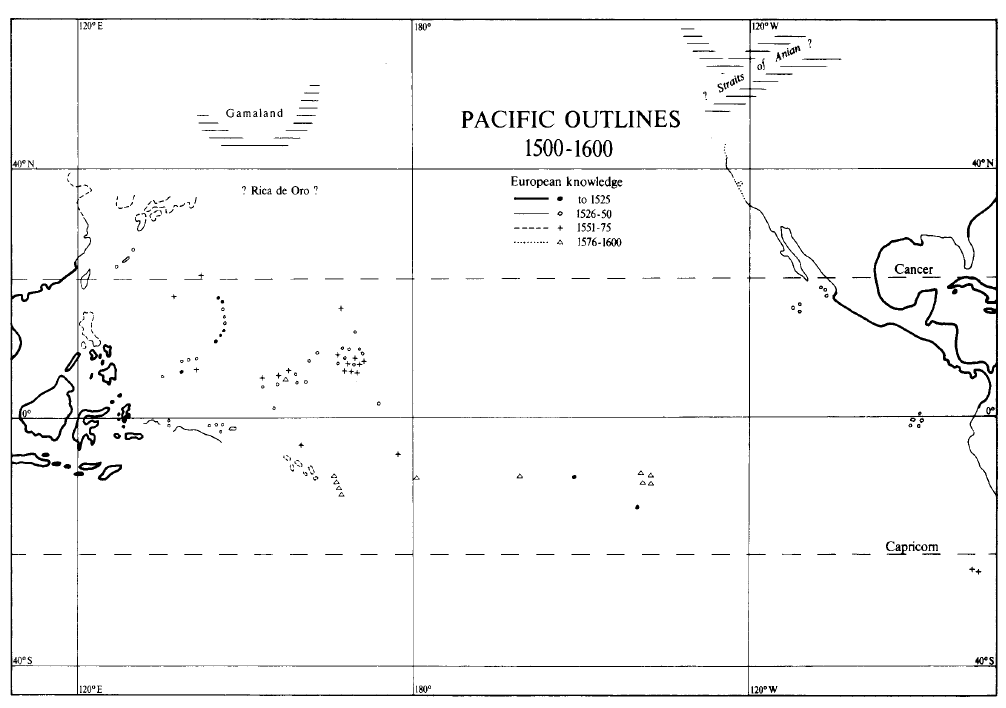

Figure 24. PACIFIC OUTLINES 1500-1600. Page 290 |

The map titled "PACIFIC OUTLINES 1500-1600" depicts European knowledge of the Pacific region from the early 16th to the end of the 16th century. It tracks the gradual exploration and mapping of islands and coastlines.

The map legend categorizes exploration into four time periods: up to 1525, 1526-1550, 1551-1575, and 1576-1600. Different symbols represent discoveries made during each of these phases.

Notable features include "Gamaland," a speculative landmass in the north, and the mysterious "Straits of Anian," which early cartographers believed might connect the Pacific to the Atlantic.

The map also shows various islands, some real and some mythical, such as "? Rica de Oro ?," reflecting European misconceptions about Pacific geography during this era.

Show more